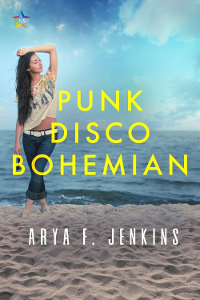

Book Description

It’s 1973 and seventeen-year old, multicultural Ali is on the run from suburbia, since her best friend has left for college and home has turned into a nightmare—a druggy brother and a mother who has hooked up with another man since Ali’s father disappeared.

Ali wants to let loose, find herself sexually, experience real freedom, and she hopes to do this in the one place she remembers being happy as a kid, when her family spent summer vacations on Cape Cod.

Provincetown has always represented freedom with a capital F to Ali. In the 1970s, Provincetown is a queer mecca, afire with gay people and a burgeoning disco scene. Ali quickly gets sucked into a partying lifestyle and starts sleeping around to gain experience. For Ali, it’s a time of growth and unraveling, of coming to terms with truth while letting go of the past. But Ali’s search could come at a price. Will she find herself? Love? Freedom? And is she willing to pay the price for them?

Purchase Links

NineStar Press: https://ninestarpress.com/product/punk-disco-bohemian/

Books2Read: https://books2read.com/Punk-Disco-Bohemian

*****

Excerpt

Excerpt

Punk Disco Bohemian

Arya F. Jenkins © 2021

All Rights Reserved

When it came time to fly, “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida” accompanied me on the radio. I turned up the volume and beat the wheel of the Rabbit with the heel of my palm. I was going to the Garden of Life. I rolled down the window and let the November wind whip my hair. Next came “Dazed and Confused.” I heard go, go, go, go in my head while the fuzzy image of a cat on my windshield, probably no more than a mirage of cigarette smoke, impelled me on.

“You begin the moment you believe you can fly,” I had written in my diary, unsure of what I meant, liking the sound of the words, enthralled with the idea of flying and beginnings.

Behind me I had my Spanish guitar and small stereo system, both gifts from Dad, red ski jacket, lamb’s wool vest, rolled-up sleeping bag, pillow, knapsack with a couple of changes of clothes and, ridiculously, a pair of white tennis culottes I’d worn months before as if I was heading into summer, toothbrush, comb, journal, pens, Erica Jong’s Fear of Flying, and a cardboard box in which were albums by Miles Davis, Dave Brubeck, and John Coltrane that had belonged to Dad, as well as my own eclectic collection by Santana, Richie Havens, Nina Simone, Deodato, Elton John, James Taylor, Cream, Joni Mitchell, and Led Zeppelin, each thing precious, a memento.

I’d taken off in the car meant to be my brother’s and mine and imagined Buddy peeved as hell, realizing he would have to mooch rides now that his wheels were gone. It was his fault for ripping me off, taking money I’d stashed inside a book from my job at a gift shop to save up for now. Who else would have done it?

When it came time to gas up, I went to the nearest phone booth to do the one thing I did not want to do that day, call home.

“Yes, operator. Collect. Mrs. Baines, from Ali. The number is 2-0-3-9-6-6-5-3-7-3.” A few rings beat slow time to my racing heart, and then someone picked up.

“Hey, Maman, Ali here.” I tried to be casual. “I want you to know I’m not coming home.”

“Ali, where are you?” Mom’s voice sounded remote. I gave no answer. Then she said, “Are you sure?”

“Nowhere. I’m not coming home. That’s all you need to know. Bye, Mom.”

The words “I hope you and Buddy will be okay” came to me, but why would I say them? Sentimentality would derail me from my goal. Buddy, Mom, and Dad were all part of the past now.

Three years before, at fourteen, I’d run off to Greenwich Village. My dress rehearsal, I think now. I felt pulled in a hundred directions at home and school, and I had nightmares from which I awoke in a sweat. In one, I saw myself crucified on a cross while being split in two. In another, I ran through woods only to come upon an empty box through which wind whistled. Why did that scare me so? The songs of the day, Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Goin’ On” and others by The Temptations, Edwin Starr, Simon and Garfunkel, and James Taylor, all spoke to feelings I tried to hide. Angst and despair were roiling the country too.

Whose hand did you reach out to, to pull you out of the darkness? I didn’t know. I listened to songs, hoping to learn. All I got was turmoil and my body telling me to run. One day, instead of going to school, I turned in the opposite direction from the bus and just kept going.

To myself I was something strange, cut out of myriad boxes, unfit to be part of anything. In first or second grade, a kid at school asked me, “Are you a savage?” I had the distinction of being the only brown kid in my class and the entire school. Maman had a dark complexion too. It would be years before I would see a Black person or anyone of color in New Canaan. Its main street glimmered white, its people were white, its clubs white, its ethos white. In this cold, subtly and blatantly exclusionary world, white middle-class women who had been abandoned, divorced, or widowed were at the bottom of the white tier, and suffered too. I got to see that close up.

As a kid I was the odd one out. My exotic, buxom Argentinean and French mother might have been in movies. My eyes were dark and fierce; my hair, black with reddish highlights, like Gra-mere’s. I have never known anyone besides us with hair naturally like that. My fluency in three languages, all of which I went in and out of easily with my parents and grandparents, added to my feeling different, like a nerd. In a family with a beautiful mother and a brother who resembled our handsome blond American dad, I was the alien.

My first time taking off, I hitchhiked toward New York City and spent my first night in a gas station bathroom. The next day I hit the West Village, where I hung with hippies, druggies, and other runaways, all of us following the same trail of dope and free music in St. Mark’s Place and Washington Square Park. I spent most of the time panhandling, my hand out, head down, leaning against buildings or standing on corners. Hardly anyone gave me a dime. Passersby glimpsed a skinny kid with hair in front of her face, wearing a tie-dyed top, jeans, and filthy Converse high-tops, a cigarette dangling from her fingers or mouth, every parent’s worst nightmare—maybe every kid’s too.

I tried going with the flow to survive. If what I went through at home was bad, this too was a kind of hell. One time, two bikers fought over me when I hadn’t said a word to either, not even given them a look. I tried not to look at people, afraid my stares set fires. One of the guys, a Vietnam vet, said whenever he rode his bike, he hallucinated trails from his acid-taking days. The burly one with a beard and leather vest called him full of shit. Somehow, I became a subject, and their fistfight drew a crowd, which allowed me to escape! Another time, a greasy-haired hippie with stained front teeth peered into my eyes and, cocking his head, inquired, “Do you know where it is? Tell me where it is, baby.” Those weird times spooked me.

On the streets, Blacks and whites commingled freely in a diverse scene, a world in which to be different was an emblem rather than mark against you. You were looked up to for it. I no longer felt isolated like at home, no longer imprisoned by false, stifling selves. Only as a runaway did I begin talking about myself and my life. There were so many stories on the street, and they interlaced like multicolored threads, a quipu of history.

“Your gra-mere must have been some crazy babe,” Leroy said after I told him how my mother’s mother, someone I loved madly, would do backbends while balancing a full champagne glass on her forehead.

“Yeah, like the Jimi Hendrix of grandmas, a surprise around every corner.”

“I love it. I love it,” he said.

Leroy was tall, slim with beautiful, expressive hands, and made me think of Hendrix, save for the mole high on his right cheek and his moss-green eyes. He had lost two older brothers, Jamal and Tyrone, in prison gang fights. After his mama died, Leroy turned to the streets, making enough to get by sewing people’s clothes, patching them up in exchange for money and stuff. He always had a basket at his side of discarded materials people had given him, along with his sewing needles and threads, and wore patchwork jeans like a colorful trip.

Ingenious and talented, he took a white silk sash and made a turban around my head. “You look like a swami”—then wrapped it around my body—“Now you are Artemis.” He scrunched up his nose, putting one closed hand under his chin. “Actually, you look more like Audrey Hepburn in the party scene of Breakfast at Tiffany’s.” We laughed. I wore the sash as a belt, then as a scarf for days.

All Leroy wanted, he said, was to live free and avoid prison. In ’63, as a boy, with his brother Tyrone already behind bars for dealing dope, he and his mother marched in DC and attended Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech.

“Air was electric, man. I never saw so many Black folks and white folks together in my life. Like heaven. After that, we got the rights.” He shook his head, full of irony. “People of color ain’t ever gonna be free long as white people run the world.”

I closed my eyes to mull his words, adding to myself, white men, as long as white men rule.

*****

Meet the Author

Arya F. Jenkins’s fiction has been published in many journals and zines. Her short stories have received several nominations for the Pushcart Prize. She is the author of three poetry chapbooks and a short story collection, Blue Songs in an Open Key (Fomite, 2018). Another collection, Angel in Paris & Other Stories, is forthcoming through NineStar Press in 2022.

Author Links

Website: https://aryafjenkins.blogspot.com/

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/aryafrancesca.jenkins

Twitter: http://twitter.com/aryafj

*****

GIVEAWAY!